Surveyors’ lines, keys to evolution and development. Keys to harbour and shoreline historical evolution and development.

Details of Site Location: There are four lines by this name, with each successive line placed further south than its predecessor. Some lines have additional or alternative names. A11 are within the Toronto Harbour area.

Boundary History: The east-west boundaries for the Windmill Lines are the Don River and the CNE grounds.

Current Use of Property: River and CNE grounds. The lines, as surveyors’ lines, are in current use. Once over open water, they are now, for the most part, over infill with developed properties.

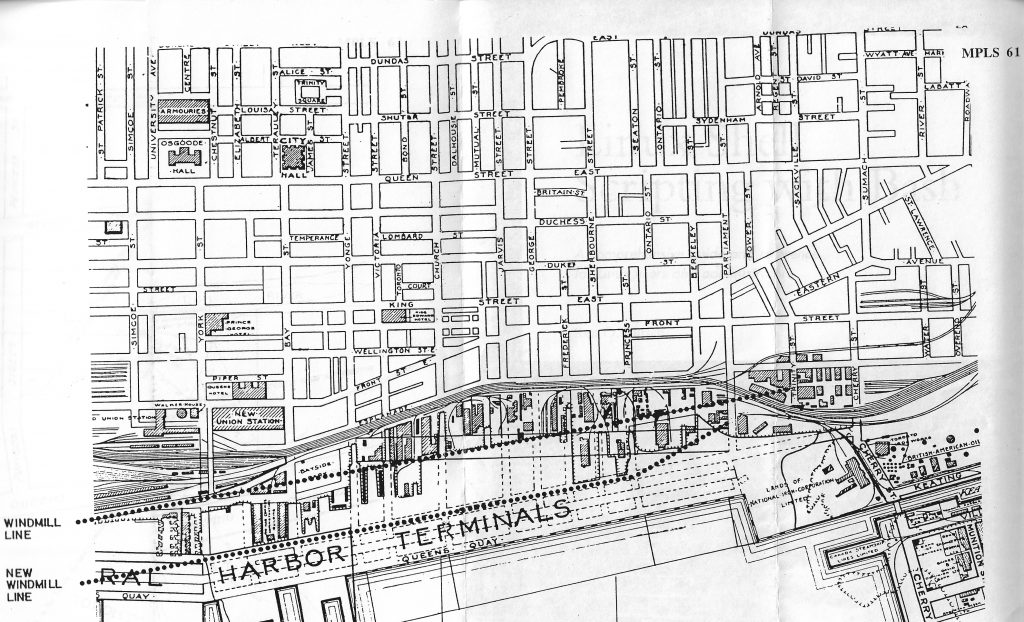

Historical Description: The following history is excerpted from the brilliant study, “Built Heritage of the East Bayfront” by Jeffery Stinson and Michael Moir, prepared for the Royal Commission on the Future of the Toronto Waterfront in 1991. It is the only technical study to succinctly present the succession of surveyors’ lines and offers maps within the document. Therefore, the lines themselves will. be simply listed here, and two maps have been copied from the Stinson-Moir document to illustrate the lines.

Windmill Line I: ran from the Gooderham and Worts’ west to Fort Rouille. The first reference to this a patent granted in 1833 to John Bishop the Elder. It was line to mark the southerly limits to which docks and other structures could be built into the harbour.

Windmill Line Agreement, 1888, was negotiated between Canadian Pacific Railway, the City of Toronto and a number of property owners or lessees, to favour railway expansion.

New Windmill Line: established by federal Order-in-Council on 12 June 1893, extended the southerly limit of the line from Parliament Street to near Spadina Avenue by 394 feet at Parliament to 644 feet at York Street.

Harbourhead Line: established by federal Order-in-Council on 24 July 1925, pushed the southerly limit 1060 feet south of the NewWi’nBmill Line at Yonge, and by 1100 feet south of the New Windmill Line at Parliament. The argument used at the time was that the line was to “control development within a harbour”.

Bulkhead or Pierhead Line: developed between 1914 and 1921 by the Toronto Harbour Commissioners in their “Progress Plan” was a line consisting of a rock levee and wooden bulkhead to give support to further reclamation from Yonge to Parliament Street. The federal government gave approval in 1926, despite strong objections, Queen’s Quay was thus developed.

Relative Importance: The importance of these lines cannot be overstressed since they represent major changes to the shoreline and harbour in response to private interests. The incremental changes have made Toronto Harbour what it is today. In the process, the original shoreline was obliterated, creeks and streams were buried or otherwise lost, early docks, wharfs, buildings public access to the waterfront and ships, were buried, and denied.

Planning Implications: Planning priorities should include markers from which the public can trace and understand the infilling of the waterfront and the position of the original shoreline, and also the early industries and shipping concerns that contributed to the city’s growth and economy. The dominance of the railways must be included in all points giving information to the public. The recommendations of the Stinson-Moir study must be reviewed and implemented.

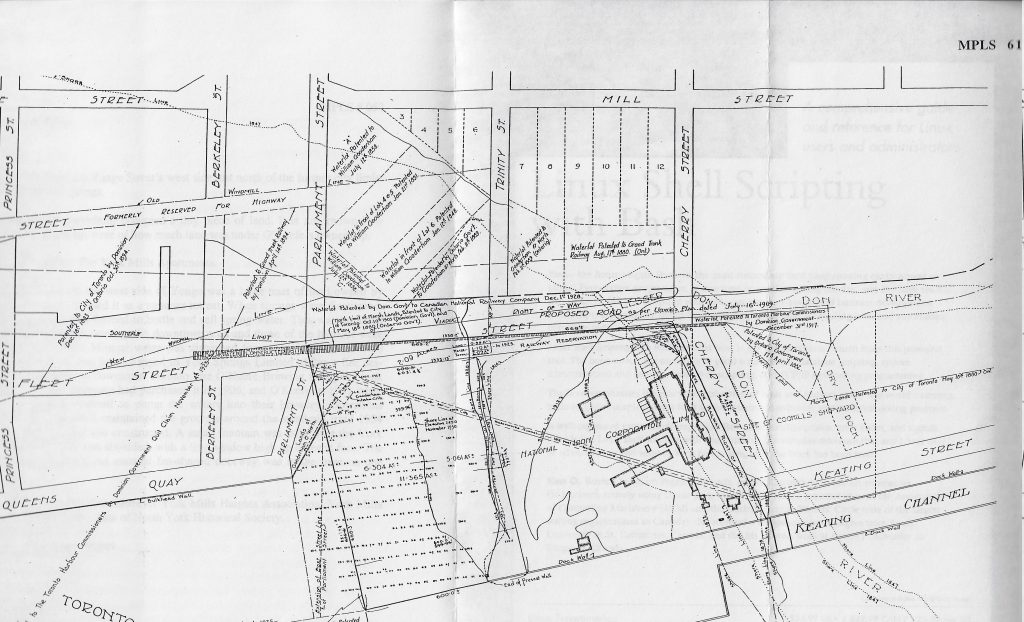

An excerpt from the Toronto Harbour Commissioners’ “Progress Plan, 1914-1921” shows existing conditions east of Yonge Street (marked by a hatch line along the wharves and unfinished edges) as well as anticipated works along the East Bayfront. It has also been marked to compare the steady movement of the limits of development – the Windmill Line (ca. 1833), the New Windmill Line (1893), and the Harbourhead Line (1925) – as well as the location of the Bulkhead Line (also referred to as the Pierhead Line, it was the site of a rock levee and wooden bulkhead wall that gave temporary support to the area’s reclamation).

This drawing shows the continual process of change that reshaped the north-east section of the Inner Harbour over the better part of a century. The limits of development shifted steadily southward from the Windmill Line to the Harbourhead Line, and the shoreline soon followed in that general direction. The breakwater that once bordered the mouth of the Don River (shown by a series of narrow lines on the plan; see also ill. 3) has been buried by fill, its function replaced by the Keating Channel to the south. The site of the National Iron Works also experienced steady change, edging west from the shoreline of 1847 (shown by the dotted lines) to the temporary limits in 1930. Dredging will expand the property to the former boundary of the marsh lands (marked by the heavy land that would soon become a dock wall) by the end of the decade.