Natural heritage river feature.

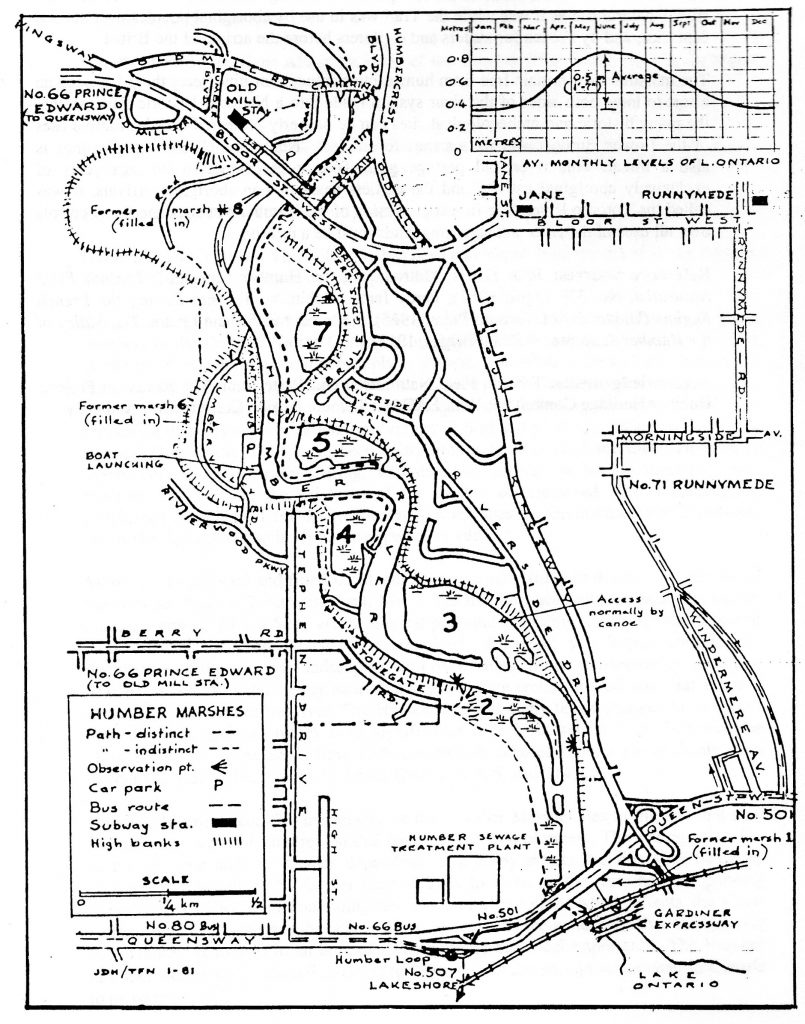

Details of Site Location: Along the route of the Humber River south from Bloor Street to the lake.

Boundary History: The boundaries of the marshes are confined to the river route within its banks from Bloor Street south to the mouth.

Current Use of Property: Primarily recreational.

Historical Description: The following has been condensed from an article in the Toronto Field Naturalist, where more detail is provided:

There were eight marshes between the King’s Mill and the lake. Later they were given numbers in the Humber Valley Conservation Report (1948) and these number are given on the attached map: even numbers apply to the west side of the river and odd numbers to the east side. Marshes 1, 6, and 8 have been irretrievably lost; the remaining marshes survive in part because of government land acquisitions following Hurricane Hazel. The remaining marshes support an amazing variety of bird and plant life, including some rare species. Historically, there have been many proposals to convert the lower Humber to regatta courses and pleasure boating, with attendant marinas. As long as these proposals continue to be made, the existence of the mashes is threatened. The Toronto Field Naturalists campaigned for designation of the marshes as Environmentally Significant Areas (ESAs) and began inventorying species in 1981.

Marsh 1 was polluted and filled in. Marsh 2 was partially filled in during construction of the Humber Sewage Treatment Plant. Marsh 3 is the most accessible. Marsh 4 is hidden and least known. Marsh 5 has archaeological potential according to historic maps; part of it is difficult to reach. Marsh 6 is completely filled in; yet despite considerable disturbance of the site and landscaping with overburden, it has archaeological potential. Marsh 7 is beautiful and mostly natural; it has important archaeological potential and also reveals an old route of the river. The Humber has had many fewer changes to its course than the Don, and old routes have significance in a river with a stone bed. For the Humber system, three ESAs have been designated: detailed reports are available from Toronto Region Conservation Authority (Numbers 4, 5, and 114).

Relative Importance: The importance of the Humber Marshes lies in the fact that they are surviving wetlands in a region that has been stripped of others. The ecological health of the Humber and the species dependent on it today reflect the fifty-year battle by Florence McDowell of the former City of York to clean up the river and the growing importance of TRCA in continuing her work of restoration, which affects the Great Lakes. In addition, the marshes that survive are close to the conditions that existed over two hundred years ago in an area of overwhelming historical importance. The Humber has been designated a Canadian Heritage River – only the second urban river in Canada to be so honoured.

Planning Implications: It is imperative the public ownership of lands along each side of the river be a priority. From Lake Ontario to Holland Landing, some three hundred historic and archaeological sites have been identified, some of national and provincial importance. One of the most important aspects of the river’s history is the Toronto Carrying Place Trail, a portage route along the east bank of the River.

The Humber Marshes are one of the few places remaining where anyone can observe the river’s natural life as it was while the Trail was in use by aboriginal peoples over several centuries, and by French fur traders and explorers before the arrival of the British.

The marshes must remain free from human interference. For nine years there has been an effort to have both sides of the river system made into a National Historic Park, so that the many historic and archaeological sites can be properly protected and destructive uses of the Lower Humber and its marshes forestalled. “Naturalizing” through plantings is also a threat. This river and portage gave Toronto its name: in the last years of exclusively aboriginal activity and the earliest years of non-aboriginal arrivals, it was called the Toronto River. The fullest protection of the Humber Marshes and firm controls over all uses of the river and adjoining lands must be a priority.

Reference Sources: John Harris, “Introducing the Humber Marshes,” Toronto Field Naturalist, No. 339 (April 1981); Percy James Robinson, Toronto During the French Regime (University of Toronto Press, 1965); Kathleen Macfarlane Lizars, The Valley of the Humber (Toronto: William Briggs, 1913).

Acknowledgements: Toronto Field Naturalists; Our Waterfront; The Rousseau Project; Humber Heritage Committee; York LACAC; Toronto Region Conservation Authority.

Humber Marshes, Toronto Field Naturalist.